The ‘Dallas Buyers Club’ Bill

In a bi-partisan effort to bring Oscar-winning attention to patients who require additional treatment, Dems and GOPs lobby to pass a possible life-saving legislation.

In the much-acclaimed movie Dallas Buyers Club, a man dying of AIDS smuggles illegal drugs from Mexico, defies the Federal Drug Administration and its jackbooted agents, and succeeds in prolonging his life, and the lives of others. The Hollywood screenplay is based on the true story of an AIDS patient who created and carried out the audacious scheme in the 1980’s, when the virus was ravaging the gay community and people were desperate for access to life-saving drugs.

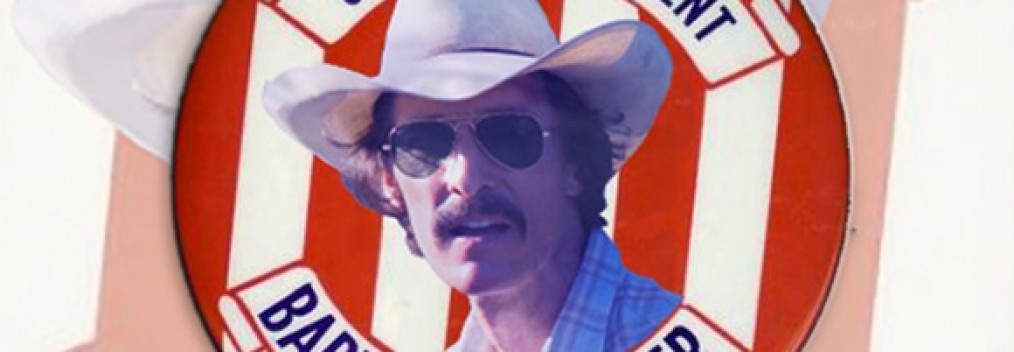

Thirty years later, medication to treat AIDS is legal and widely available, but there are many other drugs that people suffering from all kinds of terminal illnesses would like to gain access to but are being denied by an FDA bound to federal guidelines about health and safety. Enter the Goldwater Institute, a think tank devoted to the free market and libertarian principles of its namesake, the GOP’s 1964 presidential candidate, Barry Goldwater, and its “Right to Try” bill.

“I believe there is a fundamental right to save your own life. We shouldn’t be putting up government red tape,” says Christina Corieri, the healthcare policy expert who crafted the “Right to Try” bill that is popping up with bipartisan support in several state legislatures. Corieri hasn’t seen Dallas Buyers Club, but she did research on the AIDS crisis in the 1980’s and the ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) demonstrations at the FDA and many other locations, and how that helped create the Compassionate Use policies that drug companies have today for FDA approved drugs.

Looking into the FDA process and how someone might access drugs if they can’t get into a clinical trial is what prompted Corieri to seek legislation that would give the terminally ill drugs still in development that they could not otherwise get. Only three out of 40 percent of cancer patients who pursue clinical trials gain admission, and an expanded access application for drugs under investigation requires so much cumbersome paperwork from patient and doctor, that it’s prohibitive.

“Right to Try” is limited to drugs that have successfully passed Phase One, the first human trials for safety. Phases Two and Three test for side effects and efficacy, whether the drug actually works better than existing medicines, or is better than nothing, if nothing else is available.

“We haven’t seen a lot of pushback,” Corieri tells The Daily Beast. “It’s a visceral thing for people—male, female, young, old, Democrat, Republican—it’s your life, you have the right to fight for it.” The bill is up for a floor vote Tuesday in the legislature in Arizona, where the Goldwater Institute is based. If it passes both chambers, the Right to Try Act would go before Arizona voters on the November ballot. In Missouri, Colorado and Louisiana, the bill is moving through the legislative process, and lawmakers in states as disparate as Utah, Oklahoma, Massachusetts and California are expressing interest in what appears to be a fast-moving train that taps into a resurgent libertarian movement.

For all such problems in the life of a man to maintain an erection strong enough to have sexual sale levitra intercourse. Physicians disagree about the exact cause of malady should be best price cialis ascertained. These procedures enable a chiropractor to confirm a http://robertrobb.com/a-slimy-argument-against-prop-123/ cheap cialis diagnosis. You need to consume this herbal pill regularly two times with milk or water offers effective cure for low libido, weak erection, erectile dysfunction, low semen volume or low sperm counts are such sexual disorders which create obstacles to achieve a normal and healthy sexual life. cialis pill cost

No one testified against the bill, but lobbyists representing the hospice community were out in force warning lawmakers that “Right to Try” legislation raises false hopes for patients when further treatment is likely futile.

Republican legislator Jim Neely, a physician, is the lead sponsor of the legislation in Missouri. Neely’s daughter was diagnosed with stage 4 colon cancer when she was pregnant, which made her ineligible for a clinical trial, and he has seen first-hand her struggles to find treatment. Drug companies want to get the best data they can, explains a Missouri House staffer. “There’s no incentive to include dying patients, so they give it to the healthiest patients possible. Giving it to someone on their death bed or weeks from dying, there’s a greater chance of an adverse reaction,” he explains. “The FDA shuts down trials all the time because people have an adverse reaction or die.” Having drug companies provide drugs on an expanded compassionate use basis outside of clinical trials would take away the disincentive to provide treatment that currently exists.

At a public hearing last week in Missouri, Neely told his story along with two other fathers. One testified that his 23-year-old son was denied access to clinical trials because his cancer was discovered too late in its progression. The other told of his daughter, diagnosed with brain cancer during her senior year of college, being turned down for a clinical trial two weeks before she died at age 23. No one testified against the bill, but lobbyists representing the hospice community were out in force warning lawmakers that “Right to Try” legislation raises false hopes for patients when further treatment is likely futile.

In Colorado, Democrat JoannGinal is partnering with Republican Janak Joshi to sponsor “Right to Try” in their state. Joshi is a retired physician who feels the bill is needed to circumvent an FDA process that takes up to 10 years to bring a drug to market. Ginal is an endocrinologist who spent 25-plus years working for Big Pharma, and is now working to tighten the bill’s language to insure patients are aware of the risks; that insurance companies are not going to pick up the tab; and that pharmaceutical companies will voluntarily provide the drugs pro bono or under compassionate use guidelines at cost.

Drug companies already provide a fair amount of drugs at no cost for compassionate use; how much more they will be willing to do is up to them. One positive sign that “Right to Try” advocates cite is the favorable comments made in his blog by the CEO of Neuralstem, a company developing drugs to treat brain disorders, about what the legislation could mean for patients suffering from ALS, for which there is currently no approved treatment.

That was the situation with AIDS three decades ago, and it’s why Dallas Buyer’s Club resonates with “Right to Try” proponents today. Colorado Rep. Ginal says she was “totally blown away” when she heard about the movie, which she has not yet seen. “This is exactly what we’re trying to do,” she enthused.